Overview

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare and fatal condition that affects the brain. It causes brain damage that worsens rapidly over time.

Symptoms of CJD

Symptoms of CJD include:

- loss of intellect and memory

- change in personality

- loss of balance and co-ordination

- slurred speech

- vision problems and blindness

- abnormal jerking movements

- progressive loss of brain function and mobility

Most people with CJD will die within a year of the symptoms starting, usually from infection.

This is because the immobility caused by CJD can make people with the condition vulnerable to infection.

What causes CJD?

CJD appears to be caused by an abnormal infectious protein called a prion.

These prions accumulate at high levels in the brain and cause irreversible damage to nerve cells, resulting in the symptoms described above.

While the abnormal prions are technically infectious, they're very different to viruses and bacteria.

For example, prions aren't destroyed by the extremes of heat and radiation used to kill bacteria and viruses, and antibiotics or antiviral medicines have no effect on them.

Types of CJD

There are four main types of CJD, which are described below.

Sporadic CJD

Sporadic CJD is the most common type.

The precise cause of sporadic CJD is unclear, but it's been suggested that a normal brain protein changes abnormally ('misfolds') and turns into a prion.

Most cases of sporadic CJD occur in adults aged between 45 and 75. On average, symptoms develop between the ages of 60 and 65.

Despite being the most common type of CJD, sporadic CJD is still very rare, affecting only one or two people in every million each year in the UK.

In 2014, there were 90 recorded deaths from sporadic CJD in the UK.

Variant CJD

Variant CJD (vCJD) is likely to be caused by consuming meat from a cow that had bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or 'mad cow disease'), a similar prion disease to CJD.

Since the link between variant CJD and BSE was discovered in 1996, strict controls have proved very effective in preventing meat from infected cattle from entering the food chain.

But the average time it takes for the symptoms of variant CJD to occur after initial infection (the incubation period) is still unclear.

The incubation period could be very long (over 10 years) in some people, so those exposed to infected meat before the food controls were introduced can still develop variant CJD.

The prion that causes variant CJD can also be transmitted by blood transfusion, although this has only happened four times in the UK.

In 2014, there were no recorded deaths from variant CJD in the UK.

Familial or inherited CJD

Familial CJD is a very rare genetic condition where one of the genes a person inherits from their parent (the prion protein gene) carries a mutation that causes prions to form in their brain during adulthood, triggering the symptoms of CJD.

It affects about 1 in every 9 million people in the UK.

The symptoms of familial CJD usually first develop in people when they're in their early 50s.

In 2014, there were 10 deaths from familial CJD and similar inherited prion diseases in the UK.

Iatrogenic CJD

Iatrogenic CJD is where the infection is accidentally spread from someone with CJD through medical or surgical treatment.

For example, a common cause of iatrogenic CJD in the past was growth hormone treatment using human pituitary growth hormones extracted from deceased individuals, some of whom were infected with CJD.

Synthetic versions of human growth hormone have been used since 1985, so this is no longer a risk.

Iatrogenic CJD can also occur if instruments used during brain surgery on a person with CJD aren't properly cleaned between each surgical procedure and are re-used on another person.

But increased awareness of these risks means iatrogenic CJD is now very rare.

In 2014, there were just three deaths from iatrogenic CJD in the UK caused by receiving human growth hormone before 1985.

How CJD is treated

There's currently no cure for CJD, so treatment aims to relieve symptoms and make the affected person feel as comfortable as possible.

This can include using medication such as antidepressants to help with anxiety and depression, and painkillers to relieve pain.

Some people will need nursing care and assistance with feeding.

Variant CJD compensation scheme

In October 2001, the government announced a compensation scheme for UK victims of variant CJD.

A trust fund was set up in April 2001 and payments of £25,000 were made available to most affected families.

Symptoms

The pattern of symptoms can vary depending on the type of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

In sporadic CJD, the symptoms mainly affect the workings of the nervous system (neurological symptoms) and these symptoms rapidly worsen in the space of a few months.

In variant CJD, symptoms that affect a person's behaviour and emotions (psychological symptoms) will usually develop first.

These are then followed by neurological symptoms around four months later, which get worse over the following few months.

Familial CJD has the same sort of pattern as sporadic CJD, but it often takes longer for the symptoms to progress, usually around two years, rather than a few months.

The pattern of iatrogenic CJD is unpredictable, as it depends on how a person became exposed to the infectious protein (prion) that caused CJD.

Initial neurological symptoms

Initial neurological symptoms of sporadic CJD can include:

- difficulty walking caused by balance and co-ordination problems

- slurred speech

- numbness or pins and needles in different parts of the body

- dizziness

- vision problems, such as double vision and hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren't really there)

Initial psychological symptoms

Initial psychological symptoms of variant CJD can include:

- severe depression

- intense feelings of despair

- withdrawal from family, friends and the world around you

- anxiety

- irritability

- difficulty sleeping (insomnia)

Advanced neurological symptoms

Advanced neurological symptoms of all forms of CJD can include:

- loss of physical co-ordination, which can affect a wide range of functions, such as walking, speaking and balance (ataxia)

- muscle twitches and spasms

- loss of bladder control and bowel control

- blindness

- swallowing difficulties (dysphagia)

- loss of speech

- loss of voluntary movement

Advanced psychological symptoms

Advanced psychological symptoms of all forms of CJD include:

- loss of memory, which is often severe

- problems concentrating

- confusion

- feeling agitated

- aggressive behaviour

- loss of appetite, which can lead to weight loss

- paranoia

- unusual and inappropriate emotional responses

Final stages

As the condition progresses to its final stages, people with all forms of CJD will become totally bedridden.

They often become totally unaware of their surroundings and require around-the-clock care.

They also often lose the ability to speak and can't communicate with their carers.

Death will inevitably follow, usually either as a result of an infection, such as pneumonia (a lung infection), or respiratory failure, where the lungs stop working and the person is unable to breathe.

Nothing can be done to prevent death in these circumstances.

Advancements in palliative care (the treatment of incurable conditions) mean that people with CJD often have a peaceful death.

Who can get it

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is caused by an abnormal infectious protein in the brain called a prion.

Proteins are molecules, made up of amino acids, which help the cells in our body to function.

They begin as a string of amino acids that then fold themselves into a three-dimensional shape.

This 'protein folding' allows them to perform useful functions within our cells.

Normal (harmless) prion proteins are found in almost all body tissues, but at the highest levels in brain and nerve cells.

The exact role of the normal prion proteins is unknown, but it's thought they may play a role in transporting messages between certain brain cells.

Mistakes sometimes occur during protein folding and the prion protein can't be used by the body.

Normally, these misfolded prion proteins are recycled by the body, but they can build up in the brain if they aren't recycled.

How prions cause CJD

Prions are misfolded prion proteins that build up in the brain and cause other prion proteins to misfold as well.

This causes the brain cells to die, releasing more prions to infect other brain cells.

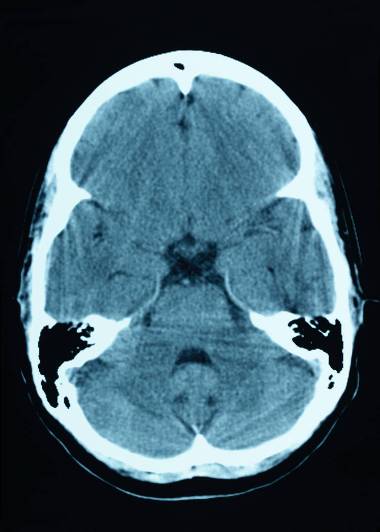

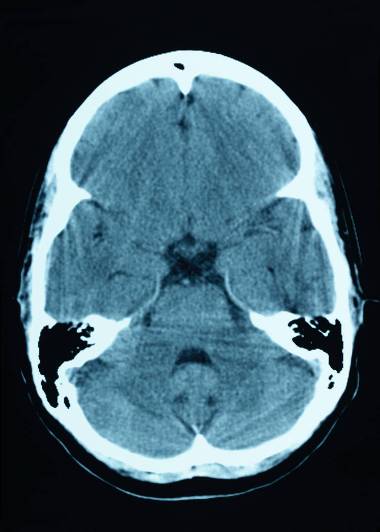

Eventually, clusters of brain cells are killed and deposits of misfolded prion protein called plaques may appear in the brain.

Prion infections also cause small holes to develop in the brain, so it becomes sponge-like.

The damage to the brain causes the mental and physical impairment associated with CJD, and eventually leads to death.

Prions can survive in nerve tissue, such as the brain or spinal cord, for a very long time, even after death.

Types of CJD

The different types of CJD are all caused by a build-up of prions in the brain. However, the reason why this happens is different for each type.

Sporadic CJD

Even though sporadic CJD is very rare, it's the most common type of CJD, accounting for around 8 in every 10 cases.

It's not known what triggers sporadic CJD, but it may be that a normal prion protein spontaneously changes into a prion, or a normal gene spontaneously changes into a faulty gene that produces prions.

Sporadic CJD is more likely to occur in people who have specific versions of the prion protein gene.

At present, nothing else has been identified that increases your risk of developing sporadic CJD.

Variant CJD

There's clear evidence that variant CJD (vCJD) is caused by the same strain of prions that causes bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or 'mad cow disease').

In 2000, a government inquiry concluded that the prion was spread through cattle that were fed meat-and-bone mix containing traces of infected brains or spinal cords.

The prion then ended up in processed meat products, such as beef burgers, and entered the human food chain.

Strict controls have been in place since 1996 to prevent BSE entering the human food chain, and the use of meat-and-bone mix has been made illegal.

It appears that not everyone who is exposed to BSE-infected meat will go on to develop vCJD.

All definite cases of vCJD occurred in people with a specific version (MM) of the prion protein gene, which affects how the body makes a number of amino acids.

It's estimated that up to 40% of the UK population have this version of the gene.

Cases of vCJD peaked in the year 2000, in which there were 28 deaths from this type of CJD. There were no confirmed deaths in 2014.

Some experts believe that the food controls have worked and further cases of vCJD will continue to decline, but this doesn't rule out the possibility that other cases may be identified in future.

It's also possible for vCJD to be transmitted by blood transfusion, although this is very rare and measures have been put in place to reduce the risk of it happening.

We don't know how many people in the UK population could develop vCJD in the future and how long it will take for symptoms to appear, if they ever will.

A study published in October 2013 that tested random tissue samples suggested that around 1 in 2,000 people in the UK population may be infected with vCJD, but show no symptoms to date.

Familial or inherited CJD

Familial or inherited CJD is a rare form of CJD caused by an inherited mutation (abnormality) in the gene that produces the prion protein.

The altered gene seems to produce misfolded prions that cause CJD. Everyone has two copies of the prion protein gene, but the mutated gene is dominant.

This means you only need to inherit one mutated gene to develop the condition. So, if one parent has the mutated gene, there's a 50% chance it will be passed on to their children.

As the symptoms of familial CJD don't usually begin until a person is in their 50s, many people with the condition are unaware that their children are also at risk of inheriting this condition when they decide to start a family.

Iatrogenic CJD

Iatrogenic CJD (iCJD) is where the infection is spread from someone with CJD through medical or surgical treatment.

Most cases of iatrogenic CJD have occurred through the use of human growth hormone, which is used to treat children with restricted growth.

Between 1958 and 1985, thousands of children were treated with the hormone, which at the time was extracted from the pituitary glands (a gland at the base of the skull) of human corpses.

A minority of those children developed CJD, as the hormones they received were taken from glands infected with CJD.

Since 1985, all human growth hormone in the UK has been artificially manufactured, so there's now no risk.

But a small number of people exposed before 1985 are still developing iCJD.

A few other cases of iCJD have occurred after people received transplants of infected dura (tissue that covers the brain) or came into contact with surgical instruments that were contaminated with CJD.

This happened because prions are tougher than viruses or bacteria, so the normal process of sterilising surgical instruments had no effect.

Once the risk was recognised, the Department of Health tightened the guidelines on organ donation and the reuse of surgical equipment. As a result, cases of iCJD are now very rare.

BSE ('mad cow disease')

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as 'mad cow disease', is a relatively new disease that first occurred in the UK during the 1980s.

One theory about why BSE developed is that an older prion disease that affects sheep, called scrapie, may have mutated.

The mutated disease may have then spread to cows that were fed meat-and-bone mix from sheep containing traces of this new mutated prion.

Is CJD contagious?

In theory, CJD can be transmitted from an affected person to others, but only through an injection or consuming infected brain or nervous tissue.

There's no evidence that sporadic CJD is spread through ordinary day-to-day contact with those affected or by airborne droplets, blood or sexual contact.

However, in the UK, variant CJD has been transmitted on four occasions by blood transfusion.

Treatment

There's no proven cure for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), but clinical studies are under way at the National Prion Clinic to investigate possible treatments.

At present, treatment involves trying to keep the person as comfortable as possible and reducing symptoms with medicines.

For example, psychological symptoms of CJD, such as anxiety and depression, can be treated with sedatives and antidepressants, and muscle jerks or tremors can be treated with medicines like clonazepam and sodium valproate.

Any pain experienced can be relieved using powerful opiate-based painkillers.

Advance directive

Many people with CJD draw up an advance directive (also known as an advance decision).

An advance directive is where a person makes their treatment preferences known in advance in case they can't communicate their decisions later because they're too ill.

Issues that can be covered by an advance directive include:

- whether a person with CJD wants to be treated at home, in a hospice or in a hospital once they reach the final stages of the condition

- what type of medications they would be willing to take in certain circumstances

- whether they would be willing to use a feeding tube if they were no longer able to swallow food and liquid

- whether they're willing to donate any of their organs for research after they die (the brains of people with CJD are particularly important for ongoing research)

- if they lose lung function, whether they would be willing to be resuscitated by artificial means – for example, by having a breathing tube inserted into their neck

Your care team can provide more advice about making an advance directive.

Specialist team

If a person is thought to have CJD, they're referred to the National Care Team for CJD in the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit in Edinburgh, or the National Prion Clinic in London, for diagnosis and care.

A doctor and nurse from these services will be assigned to liaise with local services, including the person's GP, social worker, physiotherapist and occupational therapist.

Specialist teams are available to diagnose and offer clinical and emotional support to patients and their families, and to work alongside the local care team.

A local care team may include doctors and nurses, occupational therapists, dietitians, incontinence advisers and social workers.

Care and support in the advanced stages of CJD

As CJD progresses, people with the condition will need significant nursing care and practical support.

As well as help with feeding, washing and mobility, some people may also need help peeing. A catheter (a tube that's inserted into the bladder and used to drain urine) is often required.

Many people will also have problems swallowing, so they may have to be given nutrition and fluids through a feeding tube.

It may be possible to treat people with CJD at home, depending on the progression and severity of the condition.

Caring for someone with CJD can be distressing and difficult to cope with, so many carers prefer to use the specialist services of a hospital or hospice.

Prevention

Although Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is very rare, the condition can be difficult to prevent.

This is because most cases occur spontaneously for an unknown reason (sporadic CJD) and some are caused by an inherited genetic fault (familial CJD).

Sterilisation methods used to help prevent bacteria and viruses spreading also aren't completely effective against the infectious protein (prion) that causes CJD.

But tightened guidelines on the reuse of surgical equipment mean that cases of CJD spread through medical treatment (iatrogenic CJD) are now very rare.

There are also measures in place to prevent variant CJD spreading through the food chain and the supply of blood used for blood transfusions.

Protecting the food supply

Since the link between bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or "mad cow" disease) and variant CJD was confirmed, strict controls have been in place to stop BSE entering the human food chain.

These controls include:

- a ban on feeding meat-and-bone mix to farm animals

- the removal and destruction of all parts of an animal's carcass that could be infected with BSE

- a ban on mechanically recovered meat (meat residue left on the carcass that's pressure-blasted off the bones)

- testing on all cattle more than 30 months old (experience has shown that infection in cattle under 30 months of age is rare, and even cattle that are infected haven't yet developed dangerous levels of infection)

Blood transfusions

In the UK, there have been 5 cases where variant CJD has been transmitted by blood transfusion.

In each case, the person received a blood transfusion from a donor who later developed variant CJD.

Three of the 5 recipients went on to develop variant CJD, while the other two recipient died before developing variant CJD but was found to be infected following a post-mortem examination.

It's not certain whether the blood transfusion was the cause of the infection, as those involved could have contracted variant CJD through dietary sources.

Nevertheless, steps were taken to minimise the risk of the blood supply becoming contaminated.

These steps include:

- not allowing people potentially at risk from CJD to donate blood, tissue or organs (including eggs and sperm for fertility treatments)

- not accepting donations from people who have received a blood transfusion in the UK since 1980

- removing white blood cells, which may carry the greatest risk of transmitting CJD, from all blood used for transfusions